Ten journalists from the World Press Institute visited the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism on Thursday to meet with the school’s Dean, Ernest J. Wilson, and several of its faculty. The meeting took place as part of the World Press Institute’s fellowship program, and focused on issues relevant to journalism at Annenberg, in the United States and abroad.

The 10 fellows came from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Finland, Mexico, Nigeria, Tunisia and Ukraine. Dave McDonald, the executive director of the World Press Institute, WPI staff member Frank Jossi, and former WPI fellow Priyadarshini Sen were also in attendance. This was the sixth major city stop for the fellows in a program that began in August, which also included visits to New York City, Miami, Atlanta, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. On their program so far, the fellows have met with community, business and political leaders, as well as policy experts to discuss issues ranging from the U.S. presidential race, nuclear security, policing and the changing nature of journalism today.

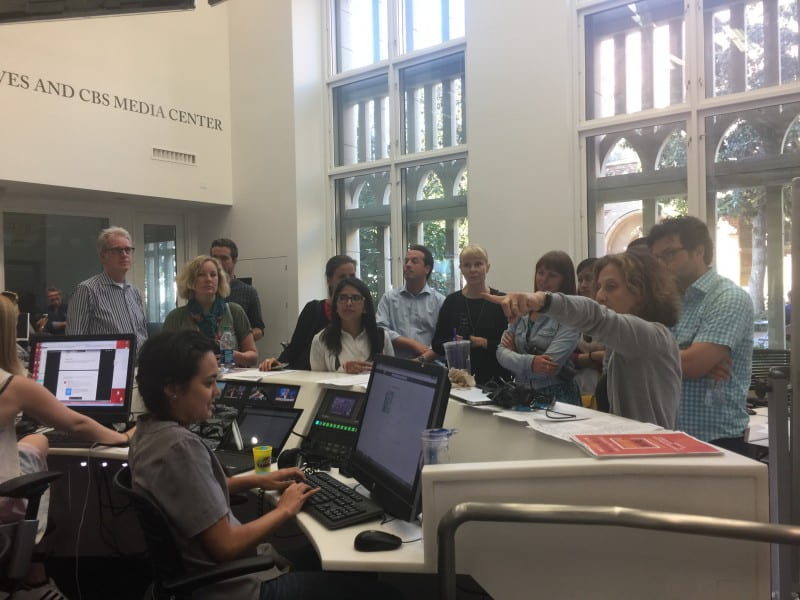

At Thursday’s round-table discussion, Dean Wilson introduced the fellows to Annenberg and talked about what the school does, who studies there and what kind of goals the faculty and administration have for training the next generation of journalists. In particular, Wilson emphasized the focus on integrating different types of journalism – including broadcast, print and digital – as well as public relations and communication, the other two majors that Annenberg offers. One way that this has been achieved is through the creation of the new Media Center in Wallis Annenberg Hall, which Wilson said allows students in these fields to collaborate and work in a shared space.

Aurelio Tomás, a political journalist for Diario Perfil in Buenos Aires, Argentina, asked what he and the other fellows should understand about reporting in the U.S. during their time here. Wilson brought up the special conditions that are present in the country as the result of the 2016 presidential election,

“It will probably reveal to you cleavages and dynamics that you would not see if you were here under more normal circumstances,” Wilson said of the election. “You’ve got Bernie Sanders on one side and Donald Trump on the other, and both are saying the same thing: the current system in America is not working for most people. If a substantial proportion of a population does something really unexpected that the media and others were shocked about, as good journalists you’ll ask what’s going on under the surface.”

The conversation also touched on the balance between reporting on events and keeping politicians accountable for their statements. Nicholas Ibekwe, an investigative journalist for the Premium Times in Abuja, Nigeria, said that the media’s treatment of Donald Trump had failed to live up to its role in holding those in power accountable for their words.

“For a long time in the campaign, the media allowed Donald Trump to have free roam – no one was fact checking him,” Ibekwe said. “The role of gatekeeper didn’t work that well with Trump, which led some people to argue that he is a product of the American media because they allowed him to ride roughshod.”

Michael Parks, who teaches in specialized journalism at Annenberg, said that for the first few months of the campaign last year, journalists didn’t try to fact-check Trump because they assumed that he would undoubtedly drop out of the race – indicating that many journalists are out of touch with a large sector of the American population that has carried Trump to the Republican nomination.

“How did journalists miss Trump’s popularity?” Parks asked. “Most american journalists are middle-class, college-educated people, and this is their world. If you produce a broadcast for you and your friends, you’re going to miss 99 percent of the country.”

According to Wilson, one way this could be remedied was to increase the representation of minorities in journalism schools. Wilson spoke about his personal mission to increase diversity at Annenberg, both among the students and the faculty, to create greater depth of coverage among the content that the school produces.

“There’s a lot of mistrust and confusion on college campuses now, and a lot of it is about who gets to be included on the campus,” Wilson said. “It’s a double problem: how do we constantly introduce more engagement with unfamiliar communities, issues, religions? How do we ensure that people at journalism and communication schools represent as wide a range of backgrounds as possible?”

The fellows will visit news outlets in Austin, Texas and Chicago, Illinois following their stay in Los Angeles, and are scheduled to attend the second presidential debate in St. Louis on Oct. 9.