This post was written by CCLP senior fellow David Westphal.

“Most U.S. print newspapers will be gone in 5 years.” – USC Center for the Digital Future, Dec. 14, 2011

“We’ll continue to have a newspaper 7 days a week for many years to come…” – Mark Thompson, CEO, New York Times, March 26, 2014

So how many more years will newspaper presses keep rolling?

I know. This is a bit of a fool’s errand. It’s impossible to know. But it’s also an important question – both a marker of the media revolution’s course and an imponderable that news startups wrestle with as they imagine their futures.

I found myself revisiting this question recently as bad news continued to spill out of the newspaper industry.

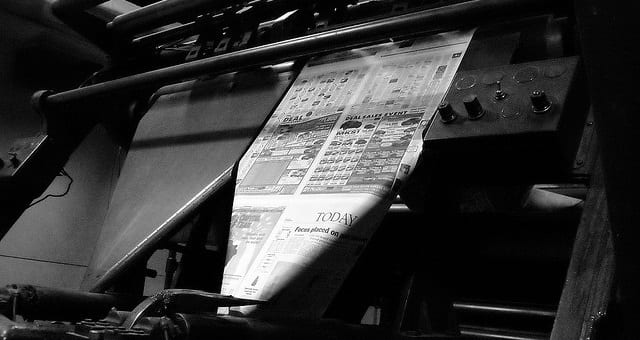

Image: “Press Room – Topeka Capital Journal – 18 September 2008” by Marion Doss

First there was the surprise closing of Digital First Media’s Thunderdome Project – a digital initiative that had drawn some of the industry’s top new-media talent, and that was seen as a possible way forward for newspapers.

Two days later the Newark Star-Ledger announced it was eliminating 25 percent of its newsroom, along with additional positions throughout the newspaper.

Ugh. Five years into a crushing economic slide resulting mostly from the digital revolution, newspaper executives had hoped that 2014 might bring a happier storyline. But print advertising revenue continues to decline precipitously, and new digital money streams just aren’t developing the way many had expected.

And yet….

Last week also marked publication of Pew’s latest State of the Media report, which highlighted the still-dominant position that newspapers have in American news production. According to Pew, daily newspapers’ share of news-related advertising revenue (print and digital) approaches 60 percent, an astonishingly still-dominant position in the market.

Given newspapering’s steep declines in both revenues and reporting resources over the last decade, the report was a bit of a reality check. Newspapers may well be on the road to marginalization in the news and information world. For the moment, though, they’re still its big financial and news-gathering engine.

And, I would say, their printed publications are not fading away nearly as quickly as I thought they might.

When I first began teaching graduate classes on the changing media business in 2009 at the University of Southern California, the Rocky Mountain News and Seattle Post-Intelligencer had closed within a month of each other, and the Detroit newspapers were about to reduce home delivery to three days a week.

It looked like the dominos had begun to fall.

Jeff Jarvis, the journalism professor at City University of New York, might have thought so, too. In May 2009, he told Spiegel Online that the current year would mark a “true sea change… More and more papers will either close or go solely online.”

There clearly has been a sea change in the five years since, with newspaper advertising down on the order of 30 percent. But no other metropolitan daily has closed. No other major newspaper has shuttered its presses. And, thanks to some revenue help from the establishment of digital paywalls, some newspapers have been reporting slightly less-awful revenue numbers in the last year. Newspapers are badly wounded, but they’re still standing, still dominant.

Why? It’s partly because they started out with an insanely dominant market position. And partly because old habits, like opening the front door and grabbing the morning newspaper, don’t die easily. But I’d guess the most important reason is that digital advertising just hasn’t developed as quickly as many expected. Print advertising still brings consumers into new-car showrooms on Saturdays; digital advertising not so much.

This has been the Achilles heel of many a news startup, and it’s not hard to imagine different outcomes for new-media ventures had digital advertising developed more robustly, and more quickly. Might Patch have had a more felicitous lifespan? Might the Chicago News Cooperative and other failed news sites found a sustainable path?

As it is, most newspapers are serving up much-diminished and often much-criticized news reports these days. But they’re still there, still delivering enough advertising firepower to bring consumers through the front door.

One telling indicator of this reality came this week, with the sale of McClatchy’s Anchorage Daily News to an online news concern in Anchorage. Alice Rogoff, owner of the six-year-old Alaska Dispatch, said this upon paying $34 million for the newspaper: “When we at the Alaska Dispatch say we’ve come to realize the value of a newspaper in print, you better believe we’ve come to realize it. We didn’t start out that way. But as we got to know this marketplace and community better, it is obvious that print plays an enormous role in a lot of people’s lives.”

It’s worth noting this, also. The Pew Report says newsrooms are now at their lowest staffing levels since 1978. While that sounds bad – and it’s been a long slide from the peak – the staffing level of newspapers in 1978 wasn’t horrible or anything.

That’s the year I joined The Des Moines Register as a sports copy editor, and coming from a tiny daily in northeast Iowa, I was amazed at the number of people doing journalism there. In the aggregate, anyway, there’s still plenty of journalistic firepower for news staffs to produce strong editorial reports.

Which is not to suggest that newspapers are riding out the storm. Hardly. The industry is extremely threatened, and the USC Center for the Digital Future may be right that its print heyday may be ending quite soon. Today, though, it remains the kingpin of news generation. At a minimum, newspapers have been given extra time to figure out a survival strategy.